Believe it or not, “The Vow” is based on a true story.

The film takes its premise from an eponymous book by Kim Carpenter that details his wife Krickitt’s recovery from memory loss following a car accident that left her unable to remember him, her husband, or their marriage.

This sounds like an episode of a soap opera, but it actually happened. It happened to two people, two very real human beings, on which it undoubtedly took a great emotional toll.

The film, however, fails to reflect this fact whatsoever.

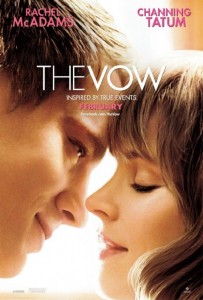

The romantic-drama dream team of Channing Tatum and Rachel McAdams star as Leo and Paige, a twenty-something Chicago couple.

They first meet shortly after Paige, a Northwestern law school dropout, moves into the city to study at the Art Institute. After a series of unconventional dates, they eventually wed—in an art museum, naturally.

This back-story is told by a series of flashbacks following the events of the film’s first five minutes, during which a large truck slams the couple’s sedan at a stop sign.

I’d like to digress for a moment to point out the utter inconceivability of this accident.

The couple’s car is stopped legally, and the truck can be seen approaching at full speed, its horn blaring as Paige and Leo make out unapologetically. This raises some questions, none of which the film ever attempts to answer.

First, why is the driver making no effort to avoid the car? Unless both the truck’s brakes and steering were disabled, anyone with common sense would try to go around it. I find it difficult to believe any sane person with an advanced driver’s license would become so enflamed with a pair of absent-minded newlyweds that he or she would attempt vehicular homicide.

Additionally, why is there no kind of legal dispute between the couple and the driver? Leo and Paige are both uninsured (a fact not revealed until more than halfway through the film), so their treatments have burdened them with massive medical debt—which the certain monetary settlement or judgment a lawsuit would provide would probably have helped assuage.

Finally, why do neither Paige nor Leo notice the behemoth big rig behind them? My experience has been that kissing, no matter how passionate, cannot induce temporary deafness and blindness—the only logical explanation as to why the horn and blinding headlights elicit no reaction from the couple.

These holes, however, are the least of the film’s problems.

Because Paige’s seatbelt was unbuckled when the truck struck the car, she was thrown out the windshield headfirst, causing a traumatic head injury.

She awakens from a medically induced coma several days later with an intact long-term memory—she can recall her childhood and contacts her wealthy parents, whom she had been estranged from for several years—but no recollection of Leo or her marriage.

In the early stages of her recovery, Paige does fairly well adjusting to the strange man claiming to be her spouse. But Leo undermines this progress on several occasions.

When Paige first reluctantly goes home with him, she finds his apartment full of her friends—none of whom she remembers. Understandably, she’s disoriented and overwhelmed, and leaves the room in tears.

Leo’s strategy of aiding his wife’s recovery introduces too much, too fast. Instead of gradually reintroducing Paige to her daily routine with him, he drowns her in a life vastly different from anything she remembers.

Instead of having any empathy for her, he gets angry when she doesn’t want to be around him.

Leo’s expectation of his wife to want to return to life with him obliterates the notion of consent. In his eyes, she is obligated to be with him because their relationship had worked so well in the past, and he’s willing to make no concessions to return to his idea of normalcy.

However repugnant this may be, Leo is not solely guilty of treating Paige like an inhuman possession.

Her parents, along with her former fiancée, are equal perpetrators.

They take advantage of her limited memory to coerce her into returning to the life she willingly left.

The fact that she was unhappy as a socialite law student has no weight—they want her back, and they use far more reprehensible means than Leo’s to achieve that end.

The despicableness of Paige’s former family is the only device the film uses to form any emotional connection with Leo—the audience is compelled to root for him simply because he’s the lesser of three or four evils.

But that does not mean he has any actual redeeming qualities.

In addition to this subtle misogyny, the film fails to introduce basic character details at the appropriate times and establishes several unresolved subplots that are largely implausible completely irrelevant to the central story.

For instance, it was unclear whether Leo had a job until 45 minutes in, when it’s revealed he owns a recording studio; and it’s not disclosed until the end of the film that Paige abandoned her former life because her father had an affair with one of her childhood friends.

Overall, “The Vow” is the worst kind of bad movie—it’s awful enough that the nearly one hour, 45 minute runtime drags by, but not so execrable as to be funny in any way.