By Noah Manskar

By Noah Manskar

Editor-in-Chief

Rape and sexual assault are the most under-reported crimes nationally—54 percent of rapes are never reported to authorities, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN).

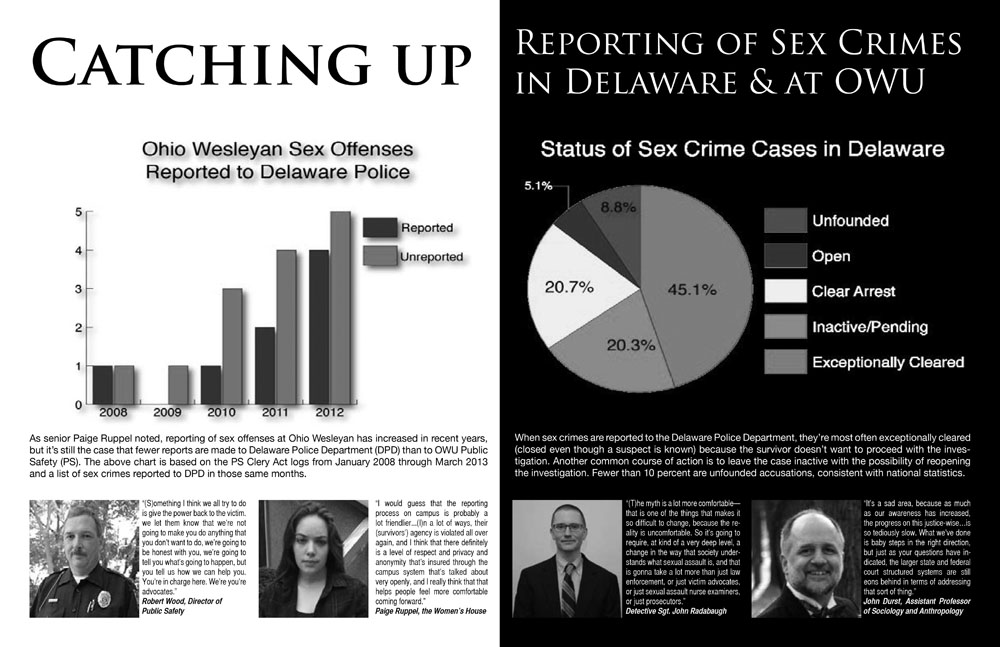

In Delaware, most that are reported are quickly closed. According to a list of all Delaware Police Department (DPD) reports of sex crimes (including dissemination and display of harmful material, rape, sexual imposition, gross sexual imposition, pandering of obscenities, sexual battery, unlawful sexual conduct with a minor and use of nudity-oriented material with a minor) between Jan. 1, 2008, and March 1, 2013, 45.1 percent of sex crime cases have been exceptionally cleared, meaning no arrest was made even though the suspect was known; 20.3 percent remain inactive pending further information. 8.8 percent were declared unfounded accusations, meaning there wasn’t sufficient evidence to support the case.

In that same time period, Ohio Wesleyan’s Department of Public Safety received 22 sex crime reports, but only six were ever reported to DPD. Of those six, four were exceptionally cleared and two remain pending or inactive. One 2008 incident was said by PS to be reported to the police, but no corresponding DPD report exists. PS Lieutenant Cathy Hursey said DPD declared the case unfounded.

PS Director Robert Wood said the department is legally obligated to file a police report for any felony sex crime reported to the university, regardless of whether the victim files a report individually. Some, like rape, according to DPD Captain Adam Moore, are automatic felonies; but others, like sexual imposition, have misdemeanor and felony levels.

Even when it’s “iffy” as to whether a crime reported to PS is a felony, Wood said the university would rather report to the police than not—once a crime reaches the felony level, there is more at stake than the victim’s decision whether to report it themselves.

“(Y)ou’re really breaking the laws of the state, and what the state says and what the prosecutor says,” he said. “If you’ve got a rampant sex offender out there committing felonies, even if you don’t want to prosecute it, we have a responsibility—we might have a responsibility to prosecute it because of the other people involved—they’re a danger to the community.”

In non-felony cases, however, PS procedure leaves it up to the survivor whether to report to the police. Wood said the department would informally notify DPD of the incident, but it is still up to the victim whether to file a formal police report.

In addition to filing a police report, PS is required to release a weekly log of every crime on campus under the federal Clery Act. According to the logs from 2008 to 2012, there was one sex crime in 2009 reported to both PS and DPD, but it is not accounted for on the annual report of aggregate Clery data from that year. Wood said the incident might have fallen out of the Clery sex offense categorization when PS compiled the aggregate data.

According to Wood, it is in Public Safety’s interest to report any “reportable” incident, but in dealing with sex crimes, the survivor’s dignity is a priority.

“(S)omething I think we all try to do is give the power back to the victim,” he said. “In other words, we let them know that we’re not going to make you do anything that you don’t want to do, we’re going to be honest with you, we’re going to tell you what’s going to happen, but you tell us how we can help you. You’re in charge here. We’re you’re advocates.”

According to Detective Sergeant John Radabaugh, DPD’s policy is similarly deferent to the survivor. They can elect to initiate a “full-court press” investigation by gathering witnesses and collecting evidence, or do nothing at all, in which case the incident becomes exceptionally cleared. Sometimes survivors will choose to leave a case inactive in case they change their mind; an inactive rape investigation can be reopened any time within the 20-year statute of limitations.

When a case is left pending, Moore said, the publicly available incident report will only contain a “media report,” a brief, basic explanation of what happened and what the status is. Most other details remain inaccessible to the public.

Moore said DPD’s procedure for sex crime cases is founded on the want not to “re-victimize victims.”

“(S)exual assaults, a lot of times those crimes are about control and power, and I think once a person’s been a victim of one of those crimes and had the loss of control or power, we as a police department do not want to force them to do something that they wouldn’t want to otherwise do,…because in a sense, we’re taking away that victim’s power and we’re taking control, which is exactly what led them to being a victim,” he said.

According to Radabaugh, this sensitivity is the department’s attempt to assuage the incredible difficulties of reporting and prosecuting sex crimes. The criminal justice system, in tandem with a culture in which being a survivor of sexual assault or rape is shameful, sets up an immense amount of hoops survivors have to jump through to be successful in procuring justice for themselves.

“Look at it this way—(when) somebody is sexually assaulted, it is probably the worst thing that has happened to them up to that point,” he said. “So they have the initial traumatic event, they get the courage up to come in and talk to me, who they had never met before, about the worst thing that’s ever happened to them—which is likely the second worst thing that’s ever happened to them. And then I ask them to go to the hospital for an exam to collect a certain amount of evidence, at which point they go in, remove some of if not all of their clothing, are asked about the event another time by the nurse, and then I sit down and talk to them about what moving forward in the criminal justice system means. And it almost invariably means talking to several members of a grand jury with a prosecutor and stenographer in the room, and once an indictment is made, possibly going to trial in front of the person who attacked them, the defense attorney, the judge, the person who attacked them’s support system, and 12 members of a jury. And that has got to be a very daunting prospect to anybody. So moving forward is not an easy thing for a sexual assault victim.”

According to John Durst, assistant professor of sociology and anthropology at OWU, the criminal justice system often places a larger burden on survivors to prove they were indeed assaulted. Because the locus of legal procedure in sexual assault and rape cases is consent, which can be subjective, a survivor pursuing a conviction has to go through a “greater sort of questioning” to prove what happened to them was technically illegal.

Senior Paige Ruppel, moderator of the Women’s House, said she feels alleged perpetrators often attempt “to prove that the survivor is guilty somehow” by asking irrelevant questions, like what they were wearing.

“That sort of rhetoric, I think, doesn’t come in as much into other crimes,” she said. “And maybe I just notice it more with these sort of situations, but I just really think that there’s something that’s not lining up.”

Socially, Durst said, American society engages in a false balancing act of the necessity of convictions and the harm of false accusations in rape and sexual assault cases. This ignores the fact that a minute minority of cases nationally are false accusations, and tips the scales against the survivor even more.

“(B)alancing that might be a little misleading—there may be two percent of all cases that are wrongly convicted, and 50 to 60 percent of cases that never even comes to the eyes of the criminal justice system,” he said. “But all that has to play itself out in a court system that’s framed in a sometimes difficult way to get a conviction.”

In Delaware, DPD cooperates with other resources for survivors to create a collaborative approach to justice and recovery. Organizations like HelpLine of Delaware and Morrow Counties, Grady Hospital’s team of sexual assault response nurses, the Sexual Assault Response Network of Central Ohio, victim advocates and others work with criminal justice personnel to make reporting, investigation and prosecution an easier process.

In Wood’s 35 years in law enforcement, he said, he’s never worked with a department more adept at handling sexual assault than DPD.

“They’re good at a lot of things, but Sergeant Radabaugh and I have worked together a long time, and I have complete confidence in this department with the way our students and our populations are treated,” he said.

Despite this, Moore said OWU students have mixed ideas about what the department does and what the best course of action is to take when deciding whether to report sexual assault. Messages from the media and peers, he said, can be “really, really powerful” in shaping someone’s perception of the police and “how interactions with the police are going to go.”

“(T)here are so many opinions out there and there’s so much in the media about what we do and how we do it, that a lot of times people have preconceived notions about what’s going to happen if they report to the police a crime or what have you…,” he said. “I think we can’t discount the power that happens, too—that they may or may not have accurate information as to what’s going to happen if they come forward.”

Wood said he feels reporting sex crimes most often does more good than harm for students.

“I’ve been here just about seven years, and I’ve never had a victim or survivor come back to me and say, ‘God, reporting to the police was the stupidest thing I ever did,’” he said. “Not one time.”

In addition to the public criminal justice system, students can also pursue sex crime sanctions through the intra-university Student Conduct system.

Michael Esler, coordinator of Student Conduct, said he receives an average of five sex crime reports each academic year; about three of them pursue charges fully, while the other two decide not to proceed. Reports can come from essentially anyone on campus—PS, Residential Life (ResLife), students who know the survivor or the survivor him- or herself.

One option a complainant has in the Student Conduct system is an informal resolution, a scheduled confrontation between the survivor and the perpetrator mediated by Esler. Few cases, Esler said, take the informal route—it’s usually reserved for situations when the survivor and perpetrator are close and want to continue their relationship.

The more common action is a formal hearing before the university’s Sexual Misconduct Hearing Panel, a group of faculty and staff who hear every sex crime case during the year they serve. As mandated by a 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter from the federal Department of Education, sex crime cases are decided using the “preponderance of evidence” standard, which is less stringent than the previous “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard, also used in criminal courts.

If a complainant is hesitant to proceed with filing formal university charges, Esler said he will sometimes ask to meet with the perpetrator and report back to the complainant following the meeting. If the perpetrator reacts unfavorably, it will sometimes convince the accusing student to move forward.

Regardless of what the complainant does, Esler said, the university is obligated by the “Dear Colleague” letter to take some sort of action. The rule is fairly “open-ended,” but something must be done to “try to correct the problem, create a better climate on campus,” or otherwise alleviate the damage done.

Overall, it is the responsibility of the Student Conduct system to balance the “three-legged stool,” in Esler’s terms, of sex crime cases—the university must “balance the dignity of the person bringing the accusation,” “protect the rights of the accused” and “protect the interest of the overall community.”

“It’s not conducive to a successful academic career if you’re always looking over your shoulder worrying about being attacked, or whether your friends are safe,” Esler said. “That’s a huge concern for us, and so whenever I’m dealing with these cases, I’m always trying to keep in mind that there are three interests here that need to be balanced and protected; and there’s no formula for it, but you have to consider all three of them all the time. That’s the challenge.”

Ruppel said she feels the university system is much friendlier to survivors than the criminal justice system, in which survivors’ “agency is violated all over again.” Additionally, the abundance of resources and the support of ResLife and PS make it easier for survivors to successfully utilize their Student Conduct options.

“…I think that there definitely is a level of respect and privacy and anonymity that’s insured through the campus system that’s talked about very openly, and I really think that that helps people feel more comfortable coming forward,” she said.

Durst said he thinks the nature of university as an institution gives it better awareness of how intimidating sex crimes are to report. OWU in particular, he said, has a good number of administrative and academic programs, like the Women’s and Gender Studies department, that focus rather intensely on the issue. However, he said, the administration has itself to look out for in dealing with the problem, since colleges and universities have only paid much attention to the problem of sexual assault on their campuses in the last 10 years.

“(T)he university might have its own interests in mind to make sure that it does investigate—as I said, should—but that it does investigate and has a lower standard, in a sense that the university doesn’t want to be portrayed as a place where sexual assault goes unnoted,” he said.

Ruppel said the intimacy of a campus environment can be daunting for survivors, especially those whose perpetrators are people they know. The weight of being responsible for a friend’s suspension or expulsion can weigh heavy when deciding whether to pursue a sanction.

“…I feel like survivors are often put in the position where they have to choose between reporting and potentially losing a friend group or losing a community that they have built on campus, or not reporting and staying silent,” she said.

Ruppel noted that there have been many more reports of sex crimes recently than in the past—PS reports say the department received 15 reports between 2011 and 2012, about twice as many as the three prior years combined. To Ruppel, this reflects the fact that sexual assault and rape are still serious problems at OWU, but also shows the campus has become more “conducive to reporting.”

Esler said he is less sure whether universities are inherently better environments for dealing with sex crimes since they “reflect the general society,” but policy changes like the “Dear Colleague” letter to create better environments for survivors by providing “more guidance” and “stricter requirements.”

According to Wood, one facet of the criminal justice system that makes prosecuting sex crimes so difficult is its foundational principle of proving guilt rather than innocence. In American law, it’s more favorable to let a guilty person go than convict an innocent one. Combined with the cultural stigma attached to sex crime, this makes it even more difficult to secure a conviction.

“Based on that type of system, it does add challenge to the prosecution and conviction of sexual assault and people that commit that crime, and that’s just part of our judicial system that we think is important, I guess, in terms of the way that it’s structured,” he said.

Reform, though, is on the horizon. According to Esler, some portions of the “Dear Colleague” letter making it easier to prosecute sex crimes made it into the newest version of the federal Violence Against Women Act; other reforms like rape shield laws and rules prohibiting the admission of a survivor’s sexual history as evidence.

Despite this, though, Esler said the reliance on “circumstantial (inferential) evidence” sex crime prosecution often necessitates and the cultural shame around being a survivor still make the legal system incredibly difficult to navigate.

“(T)here are reforms out there, but there’s still a stigma, and I think people reporting it will sometimes shy away from it because the system can be harsh on them…,” he said. “A strong defense attorney will try to turn the tables and somehow make the person filing the complaint the guilty party.”

Additionally, according to Esler, most sex crime laws are enacted on a state-by-state basis because they are out of the federal legislature’s jurisdiction.

The lack of federal power has resulted in an inconsistent “patchwork federal system”—some state laws are easier on victims, while others make it more difficult to get a conviction. Therefore, it’s left to administrative agencies like the Department of Education to use their fiscal “leverage” where they can to make policy friendlier.

Durst said he thinks the reason behind the discrepancies between university and legal systems is procedural as well as structural—it takes a lot of political effort to change criminal statutes, so it’s rarely done.

“(I)t’s a very political—good and bad—process to do anything in terms of creating, modifying, doing anything in terms of the actual criminal code and the processes,” he said.

Regardless of administrative or legal reforms, Durst said. American culture and law are still patriarchal—men make the laws and dictate how they will be enforced. Because law is a reflection of societal values, Esler said, it will take a deeper cultural change to make the legal process easier for survivors.

“(A)s long as people don’t take rape and other sexual assault as seriously as they should, as long as men believe that this is something that isn’t that serious, we’re not gonna be able to make huge reforms,” he said. “So ultimately I think it has to be a societal thing, where people respect the dignity and privacy and integrity of other people, and unfortunately too often that isn’t the case.”

According to Radabaugh, American culture has a lot of myths about what sexual assault is—that you’ll only get raped if you’re in a bad part of town at the wrong time, and that it’ll be a surprise. These contradict the reality that a perpetrator is more likely to be someone the survivor knows. This avoidance of reality is why it’s so easy to believe those myths.

“(T)he myth is a lot more comfortable—that is one of the things that makes it so difficult to change, because the reality is uncomfortable,” he said.

“So it’s going to require, at kind of a very deep level, a change in the way that society understands what sexual assault is, and that is gonna take a lot more than just law enforcement, or just victim advocates, or just sexual assault nurse examiners, or just prosecutors. That’s going to take a lot of work….(O)n one hand that can be very frustrating for me, because I’m inside this working every day; on the other hand, I can see how it is comfortable to believe those myths.”

While awareness has undoubtedly increased, Durst said, the legal and cultural systems in place are “tediously slow” in making changes suited to that awareness. There are resources in place, but their limited reach and the patriarchal nature of the culture make it “a long ways off from being equitable or just.”

“What we’ve done is baby steps in the right direction, but…the larger state and federal court structured systems are still eons behind in terms of addressing that sort of thing,” Durst said.

To Ruppel, the problem is as relevant on the individual level as the systemic level—the amount of “irrelevant” questioning survivors have to endure in the court of public opinion is just as onerous as it is in the criminal justice system.

“(S)mall things like that that are just ingrained because of the rape culture we live in—that needs to change,” she said.