It started in the 1980’s. I wish I could claim the idea for our Tent City protest was my own, but I recycled the idea from the tactic used by students on campuses across the country, as they demanded their universities divest from South Africa and cease financial support for their system of apartheid.

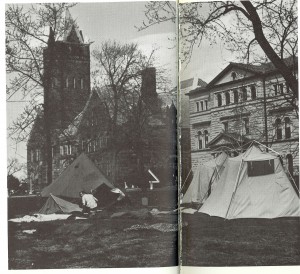

Late one night during finals week last semester I flipped through an old copy of OWU’s yearbook that was lying around Beeghly Library. In it I found a campus very different than the OWU I had experienced. There was picture upon picture of students protesting in tents, marching, touting megaphones and picket signs; the spirit of activism was alive and well on campus. What started as a means of procrastinating from studying became a source of inspiration.

Yes, this is about sustainability, but it is also about students having a voice on their campus. We are not just receptacles of knowledge, here to get an education for four years and then move on to bigger and better things. We are part of the Ohio Wesleyan community. As Sagan speaker and former Sierra Club director Michael Dorse, said to me, “They say to you, ‘You are only here four years so you can’t get anything done. But that is a trick.” In education we call it the self-fulfilling prophecy.

In the 1970s, when the students were upset by their lack of representation in the university’s policy-making, they pitched tents and formed “The People’s Park.” This led to drastic changes—most of which were only temporary—including allowing students to be more involved in deciding tenure, planning new buildings and academic scheduling. They even opened a faculty to meeting up to the student body, which drew a crowd of 300 students. One of the lasting impacts was getting a student seat on the Board of Trustees, a practice that continues today.

In the 1970s they were able to create change because there was a feeling among their cohort that change was possible. They didn’t back down, they didn’t expect instant results and gratification, they were in it for the long haul and they were willing to take risks.

So yes, we can change the world, but we have to believe we can. The effects of climate change are real. We have already experienced a marked increase in extreme weather, we have more carbon dioxide in our atmosphere today than anytime in the past 800,000 years and the number of species that are classified as endangered is increasing at an alarming rate, to name just a few of the devastating impacts of global climate change. Clearly, we are already changing the world. So why don’t we instead change the world for the better?

As a history major, I know that history, like nature, is cyclical. The students were successful more than once before. The university pledged in the 1980s to divest from South Africa. There is no reason we can’t do it again. Many years from now, if mankind is still around, will we say that OWU was part of the problem or part of the solution? And if we are part of the solution, then perhaps some students in 2040 will look back and we will be the ones to inspire, as the fight for global justice through local action continues.