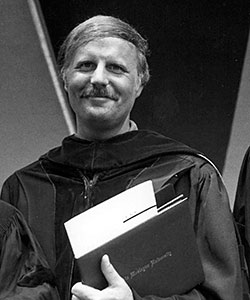

Many students know William Louthan as the politics and government professor with a penchant for constitutional law and judicial politics. But in his 43-year tenure at Ohio Wesleyan, he has also served as provost for 14 years and president for one.

Louthan has much to say when it comes to how Ohio Wesleyan has changed in the last few decades, what it was like to be the Provost and then thrust into the presidency, and what “crucial ingredient” is lacking in American politics today.

The interview has been condensed for space.

Q: You’ve served many different roles on campus since you began working here in 1972. What brought you to OWU back then?

A: My Ph.D. adviser had graduated from Ohio Wesleyan back in like 1919 or something, and he wanted me to teach at his alma mater. So, he called me and encouraged me to apply for this job, which I did. I came here in June of 1972.

Q: What has kept you at OWU for over 40 years?

A: Well, it’s interesting because when I came here I had never been affiliated in any way with a small college. I was an undergraduate and graduate student at Ohio State, went to law school at Michigan [State University], and I taught at American [University] in Washington D.C. So, although I was a native of Ohio—I’m from Akron originally—I really didn’t know much about small liberal arts colleges. I had never lived in or around a small town. But, after having been here just a short period of time, I concluded that being a liberal arts educator was the best of all possible jobs.

Q: Why is that?

A: I think it has mostly to do with the possibility of teaching exclusively undergraduate students, so it’s not a matter of training students to do or be anything, but rather to take people who are between 18 and 22 years old who may or may not yet know what they want to do with their lives and contribute to giving them the kind of education that will serve them well pretty much no matter what they do. I say that and it sounds simplistic, and it’s not something that would ever have occurred to me before I got here. It’s something I sort of learned on the job.

Q: In what ways has OWU changed since 1972?

A: Obviously, the campus appearance has changed a great deal. And I’m not referring simply to the new natatorium, or the new fitness center, or the refurbishment of Merrick. When I came here there was no JayWalk, for example. Chappelear Drama Center opened its doors the first month I was here… The student population is smaller now. The faculty and staff population is smaller now. But, the things that do matter haven’t changed I think. I noticed when I came here that we had an extremely strong faculty. During the years that I was the Provost, I was convinced we had the strongest faculty of any liberal arts college of our sort. And now that I’m obviously toward the older end of the generation of faculty members, I look back on where we were and where we are now and I’m just proud to say I think that among our peers in the GLCA [Great Lakes College Association], the Ohio Five, the United States generally, you’d be very hard-pressed to find a stronger teaching faculty than we have here… We provide the best possible kind of liberal arts education, and I don’t think that’s changed…

Q: You were also Provost for a number of years. What was that like?

A: The Provost is the chief academic officer and the second ranking executive officer. The part about that job that I like and I think the reason that I aspired to do it was the academic side. I think that at a truly strong college or university…there are two things the faculty must be in control of. One of them is faculty personnel—the hiring, promotion, pay and benefits of its faculty. And the other is the substance of the curriculum. Faculty personnel policies should be developed by the faculty. Academic and curricular requirements should be developed by the faculty. Those things should be done without interference. And it’s the Provost’s job to work with the faculty to implement faculty personnel and academic policies, so that’s why I aspired to do it and that’s why I did it for 14 years—simply because I enjoyed it.

Q: Why do you no longer hold that position?

A: Fourteen years is probably long enough for anyone to do it… I was Provost from 1991 to 2005, and in ’93 to ’94 I was acting president. That was a job that I did not enjoy, but since the Provost is the second ranking executive officer…and the prior president left to go to another job, and it takes frequently a year or more to search for and hire a new president…whoever the Provost happens to be then would normally be the acting president. So, that was the way it was. I more or less had to agree to do it, and I did it. Without boring you with the details of what it takes to be a college president and what you have to do if you are a college president, I can tell you I didn’t like it much at all. I was happy to return to being Provost when that ended. But, I was still relatively young when I became Provost, and I never imagined that I would be Provost my entire career. I always expected that I would come back to teaching at some point, because that’s my first love.

Q: Did anything happen during your year as President that still stands out to you?

A: There were no major issues of crisis for the college as a whole during that year, fortunately. The reason I remember it being a very difficult and demanding year was that, while I was acting president, I was also serving as Provost. We didn’t hire someone to be acting Provost, so I was Provost and acting President at the same time. And, I was also on the search committee for the president, so it was almost like a third job…so I just think of those 12 to 15 hour days doing a lot of stuff that wasn’t very much fun. But that’s just the personal side of it… One thing that immediately comes to mind is that there was a student death that occurred on campus, which is always a tragic event, and having to deal with that student’s parents and friends and faculty and advisers…was very, very difficult. It was a suicide, so that’s part of what made it very, very difficult… The most painful thing I remember about that entire 14 months was that student’s death.

Q: How did your interest in politics and government begin?

A: You know, I think it was so long ago it is hard for me to identify a time. I can remember as early as the mid-1950s not only being interested in elections, but thinking that I wanted to be a lawyer and go into politics myself. And, I was just fascinated by political figures and elections. I didn’t understand a lot of it then. Of course, the way you learned about it back then was much different. There were only three TV networks, black and white TV, and 15-minute to a half hour news programs, and so you weren’t saturated with political news and information as you are in the modern era… Having a law degree seemed to be one of the ways you got into politics, and so long before I had any idea what it would actually mean to be a lawyer, I aspired to get a law degree simply so that I could get involved.

Q: You specialize in judicial politics and constitutional law. Is there anything regarding those subjects that most Americans don’t know, but should?

A: Lots of things. Frequently people will ask me, “Does it ever bug you when you’re either teaching common law or talking to people about common law when people articulate strong positions on the Supreme Court decisions that you disagree with?” And my answer is always the same: it doesn’t bother me at all when people express informed opinions, no matter how different from my own personal views they may be. What bothers me is people asserting facts, history, contents of decisions inaccurately. Clearly, all Americans are entitled to their own opinions, but they are not entitled to their own facts. I think one of the major problems we have in American politics and government today is that too many people, both on the political left and the political right, talk only with other people who think the same thing they do. They hear a story about what the Supreme Court has decided or what Congress has done that’s compatible with their own political ideology, so they come to believe it… But the fact is that they are ignorant, and I use the word ignorant here in a non-pejorative way. Simply, they don’t have the knowledge. They don’t know, but they think they know…

Q: Any advice for students looking to pursue careers in politics and government?

A: I think anyone doing that today needs to develop a tolerance for ambiguity and, perhaps more than ever before, a pension for civility. The most notable, crucial ingredient American politics is lacking is civility…in our political discourse. Motivation to change the world and make it a better place is a noble objective, but without a tolerance for ambiguity and a pension for civility you’re not going to get very far, no matter how noble your objectives.