By Noah Manskar

By Noah Manskar

Editor-in-Chief

Alcohol and adulthood are strange bedfellows at the uniquely American institution of the residential university.

With entrance into college—and the departure from home it often necessitates—comes a degree of independence and a select few accompanying privileges. Students thrust themselves out of their parents’ watchful gaze and into a universe where alcohol, the mystical substance of their youth, is readily available. It’s a thrill to be able to make the choice whether to partake, a decision previously reserved for adults.

With this opportunity, however, comes a risk. For at least half of the average Ohio Wesleyan student’s time at the university, it’s still illegal to consume or possess alcohol even when it’s accessible—the law says the legal age is 21, and public and private authorities enforce that law. Despite the independence they have and adult choices they’re able to make, students are still not considered full adults in the eyes of the government.

“The legal threshold that enables young people to engage in adult-like behavior operates as rite of passage,” said Dr. Harry Blatterer, sociology lecturer at MacQuarie University in Sydney, Australia. “Hand in hand with that, legal consumption sends the message to young people that once you cross that threshold you are considered an adult.”

Blatterer’s research specialty is “sociology of the life course,” particularly social constitutions and constructions of youth and adulthood. He has published numerous scholarly articles and a full-length book, “Coming of Age in Times of Uncertainty,” on contemporary adulthood.

According to Blatterer, legal drinking’s tie to adulthood is partly social and partly psychological. In the post-World War II era, when the modern convention of adulthood was formed, the drinking age stood at 21. But successful efforts in the 1960s to lower the voting age affected the drinking age, as well—it became 18, concurrent with the age of conscription.

“You can argue that at a time when the people were needed for the war effort, it made sense to make them feel like they grew up,” Blatterer said.

However, with advances in psychological research and a rise in drunk driving following the change, the age was returned to its former status to protect the public from youthful recklessness and protect youth from themselves.

“We have really internalized the categories of developmental psychology that very strictly categorize the maturity people are supposed to have in their lives,” Blatterer said.

The alcohol-adulthood connection, though, is not universal. Sophomore Ashley Cole said the law and her personal attitudes towards drinking have not formed a bond between the two in her mind.

“I’ve just never measured adulthood by being able to drink, personally,” she said. “…I guess I can see how other people think there’s a relationship. I can see how other people feel mature when they drink. I’ve never really wanted to drink myself. I kind of want to, but when I’m 21, just because that is the law, and if the law was 18, I probably would drink now and then just to try it. But I feel like we just go with what’s allowed and what’s not allowed and don’t really think about the implications, I guess, on maturity.”

Cole grew up in Ashtabula, Ohio, with parents who drank “once in a great while”—there was rarely alcohol in their home, and she was seldom around people who drink until she came to OWU. She said this influenced her choice not to drink until she turns 21, and that she views drinking to excess negatively.

“When it’s just a little bit now and then, I understand, but when people get drunk that’s when I have a problem, because to me, that’s showing that you’re not mature,” she said.

Additionally, developmental psychology isn’t field that has something to say about alcohol’s role in adulthood. According to Karen M. Herrmann, Jungian psychology says alcohol has negative effects on the development of one’s consciousness, as well as the physical brain.

“It makes people unconscious,” she said. “I think the whole process Jung focused on is becoming a unique individual—conscious, changing and expanding.”

Herrmann received her post-graduate degree in analytical psychology from the International School of Analytical Psychology in Zurich, Switzerland; she also studied at the C.G. Jung Institute. She practices in Columbus, Ohio, specializing in spirituality, depression and substance abuse.

According to Herrmann, the Jungian challenge for young people is to develop a balance in habits like alcohol use in order to fully develop one’s consciousness and relationship to the world. This can become difficult when engaging in drinking as a way to “feel connected to their peers.”

“I think the task for a student is to develop their ego and who are they in the world, and it is about testing limits and realizing what’s not healthy and what is,” she said. “But I think if they find their way in the world and get established, it’s later typically what Jung calls the self—it’s a spiritual process where they let go, but they still need their ego.”

According to Tony Buzalka, a senior from Wadsworth, Ohio, the transition from illegal to legal drinking causes a shift in self-perception more than others’ perceptions of one’s adulthood.

“The first couple times you drink legally, you’re like, ‘Oh, I can do this. Look at me, I’m all grown up,’” he said. “But I’d say people around your age also change. They’re like, ‘I can legally drink now. Cool.’ Your parents and other adults just still see you as—I wouldn’t say they necessarily recognize you as an adult. I still think that we’re looked at as still young and pretty immature, especially since a lot of people, when they’re legally able to drink, don’t usually make the correct decisions while drinking.”

When he was underage, Buzalka said, alcohol was “mysterious stuff,” an enigmatic substance vital to having a good time. But coming of age and experiencing its effects broke down those facades.

“It was kind of something that I was supposed to do, and once I turned 21 it kind of lost the mystery,” he said. “There was just kind of a sense of maturing—I don’t need this; it’s just there. I think just the idea of something I’m not supposed to have—I think that affects everyone, the idea of forbidden fruit.”

For senior Ellie Bartz, the legal dividing line between her and alcohol was clear. Growing up in Sterling Heights, Mich., her parents were never particularly restrictive about drinking themselves, but it was implicitly articulated that it would only be acceptable for her to drink after she turned 21.

“I guess it’s kind of one of the last big milestones between being a teenager or being an adolescent, and a responsibility but also a privilege that you now have when you can drink legally,” she said. “The duality between them—it’s a privilege, but it’s also a responsibility, because you have to not—you don’t have to, but you can if you use the privilege—but you’re kind of expected not to.”

—

Freshman Claudia Bauman spent 11 months in Germany with the Rotary Exchange Program after graduating high school in 2011. She lived in Bautzen, a town near Dresden in the former East Germany. The cultural differences she noticed between American and German attitudes about alcohol in her time there were vast.

“Here versus there, in Germany, it’s a lot more—I don’t wanna say encouraged, but accepted,” she said. “Young, young kids start drinking and they just grow up with it. It’s just another part of life, versus here, I feel it’s a whole other world.”

German law says youths can buy beer and wine for themselves at 16 and all other alcoholic products at 18. Bauman said alcohol is introduced to children long before they reach the legal age, and parents often provide them with alcohol.

“13 year-olds-start sipping on beer, 16 year-olds-can buy it themselves, and they’re still at home,” she said. “They learn their limits a lot earlier, and they just have control over it.”

Kate Lewis-Lakin, a junior from Chelsea, Mich., noticed similar differences when she studied abroad in Cork, Ireland, during the fall semester.

“I think it’s just more acceptable, part of the culture, not ever really made to be a bad thing; where I think it is here people do abuse it when they’re in college, younger, and also because it’s not legal until you’re older, it’s a lot more demonized as a bad thing,” she said.

Lewis-Lakin said Ireland’s drinking culture is “something they are proud of.” Beer brewing is widely practiced, and the nation’s stouts—dark beers made from malt or barley and hops with an alcohol content of 7 percent to 8 percent—are its darling craft. Because of this, both natives and foreigners invariably flock to pubs.

“Pubs are gathering places, and you are really not expected to drink in a pub if you really don’t want to, especially on a weeknight; but they are the places where people gather together,” Lewis-Lakin said.

Emily Slee, a freshman from Melbourne, Australia—where the drinking age is 18—has experienced the stricter American values toward alcohol as well as the more liberal Australian attitudes. She was born in Melbourne, moved to the U.S. around age 4 or 5, and then back to Australia for high school; her parents currently live in the states.

She said because her mother is American, she is generally reluctant to skirt the legal drinking age and serve her a glass of wine with dinner, but her Australian father is less hesitant because of the Australian attitude.

“I know a lot of Australians are a lot more laid back, so they kind of have a very blasé attitude towards it, and I know that in my family particularly—or just America in general—you tend to see more of the conservative side,” she said.

It was hard for Slee to relinquish the ability to drink legally when she returned to the U.S. for college. She said the lack of independence in getting herself alcohol to consume casually makes her feel less mature. To her, the discrepancy is “a bit silly.”

“It’s frustrating,” she said. “I don’t mean to sound like an alcoholic, because I’m not, but it’s more of the fact that if you want go have a drink with friends or if you want to just drink casually with your parents, you just can’t.”

Lewis-Lakin also found it difficult to have national borders affect her status as a legal drinker. She was well over the Republic of Ireland’s legal age of 18 during her four months in Cork, the country’s second-largest city, but she still has another year before she can order a stout with a meal in the United States.

“(T)hat’s just annoying, because I am a responsible drinker…and just the fact that I’m not able to drink in a restaurant here frustrates me, and that’s just based on the year I was born versus any sort of experience or anything like that,” she said.

In American law and culture, the age of 21 is the point at which people are deemed instantly ready, physically and socially, to consume alcohol. In contrast to Germany, Ireland and Australia, there is no gradual phasing-in of alcohol into one’s life.

According to Mainza Moono, a freshman from Lusaka, Zambia, this attitude is also different from the convention on the African continent. Moono said he chooses not to drink, but has observed how people use alcohol in American and African culture.

“I think for us, the ‘you’re ready’ time—there’s no line,” he said. “You’re ready when you think you’re ready. But I feel it’s something you baby-step into. You slowly start doing it—it’s not like, ‘Tonight I’m starting to drink, I’m going to get wasted.’ That’s how it would be for the first time for a high school student, whereas for us it would be, ‘Tonight I’m drinking, I’m gonna have one beer, that’s it. Next week, maybe I’ll have one and a half, or I’ll try wine next week.’”

Bauman said the German tradition is similar, but alcohol is presumed to be a part of the eventual adult’s life. This allows people to understand how alcohol affects them earlier on so they can learn how to safely consume it. This stands in contrast to the American practice of presumably having none until age 21, and then taking full advantage of the new drinking privilege.

“(Y)ou start off drinking little by little—sips as a child to maybe a glass of wine or half a beer—slowly progressing forward,” Bauman said. “When here, a lot of people, their first experiences with alcohol, they don’t just have a sip; it’s more than that. They slowly build up just a tolerance, let alone knowing how much they like to drink or how much they can drink, what type of alcohols agree with their bodies versus not, what can mix—they know all that stuff by age 17, 18.”

According to Bauman, the more steady transition into alcohol use develops a higher sense of responsibility around it in German culture. She said the people she met there were “a lot less rowdy when they drink” than their American counterparts.

“There were a lot of parties I was at where people were like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’ve got to be careful cause I’m drunk and I can’t make a mess, cause otherwise somebody else is going to have to clean it up,’” she said. “Or if they make a mess, they immediately start to clean it up themselves, when you don’t see that as much here—more run away from it. They’re just so responsible for so many different things.”

Moono said alcohol necessitates an elevated responsibility in African culture, as well. It’s escalated even further by the fact that going to a party or club where alcohol is served means driving, and driving means keeping consumption at a safe level.

“So even the extent to which you drink—it doesn’t mean you’re free,” he said. “…But the fact that you’re in someone else’s car means that you have to exercise some responsibility as well, cause you have the luxury of being able to go out.”

—

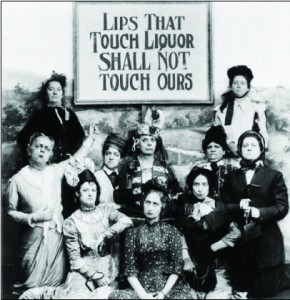

A 1912 photograph of temperance advocates displaying the slogan of the Anti-Saloon League, a 20th century prohibition lobby group. The League worked alongside other groups, like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, to pass the 18th Amendment in 1920.

But when Blatterer was a boy in Austria, he would sit with his father in pubs from the time he was eight years old. This early exposure to alcohol and what it did gave him an idea very different from many American youth.

“For me growing up as a child, first of all I saw that adults, when they drank too much, just became boring,” he said. “So that kind of means that I didn’t develop a fascination with alcohol, but it also demystifies this notion that alcohol is something very special.”

Blatterer said he thinks this “cultural prohibition” leads many young people to seek it out before they reach the legal age. Once they turn 21, then, they’ve overcome their initial fascination with alcohol.

“So we classically see what we call binge drinking—consumption of large amounts of alcohol—and that’s classically an Anglo-American idea,” he said. “The prohibition backfires, basically. On the one hand it’s saying it’s dangerous, but on the other it’s saying it’s something very special.”

OWU senior Buzalka said he thinks the media’s portrayal of drinking, especially in a college context, makes American youth think alcohol has a power to enhance social situations. He said peer pressure contributes, too—even without direct badgering to consume alcohol, there’s still an implicit assumption that those who abstain are “misfit(s).”

“It makes people kind of put it on a pedestal and makes it seem like everything’s going to be better—social situations are going be great when you’re drinking, and you’re going be more popular cause you’re drinking,” he said. “But once you’re 21 and you’re able to drink whenever you want and no one else has control over it, I think it’s a big thing, just to—I guess you see it for what it really is.”

Bartz, another OWU senior, said alcohol’s cultural mystification affected her ideation of how she would celebrate turning 21—since the event represents a conferring of great privilege, she expected it to feel more significant than it turned out to be.

“(I)t made it seem like it was this big, epic deal, and going to the bar for my 21st birthday and ordering a drink was the most chill thing in the world,” she said. “…And that was really strange for me, because I felt like it was going be this big—not life-altering moment, but just this big moment, and it really wasn’t. It was just me and my friend and the bartender and the four other people who were there.”

Cole, a sophomore, said she thinks some cultural demarcations of when certain behavior are “arbitrary,” but understands the restriction on alcohol. Perhaps the drinking age could be lowered to 18, she said, but to go any lower would be to tread into dangerous social and behavioral territory.

“I think it’s good that kids in high school can’t, except maybe the seniors that are 18, because you’re still trying to figure out life, what’s going on, like dating and boys—all that stuff,” she said. “I see why adults want to keep it away, but they’re really not able to anyways.”

To junior Lewis-Lakin, rearing children to have moderate attitudes about alcohol is as crucial as effecting policy. She said she thinks allowing children to occasionally experience alcohol gives them a “good foundation” for beneficial drinking habits. Or, as her parents did, they could simply exhibit healthy, moderate habits for their children to follow.

“I just think it’s important for parents to model healthy drinking behavior for their children, whether or not they drink with them,” she said. “I think that was definitely a big thing that I did get from my parents, because they enjoy alcohol, but aren’t crazy about it. So that just set me up to have good drinking, so I think parents, guardians, whatever they may be—it’s as important to model that as it is to maybe change the law.”

Even if the law were to change, Bartz questions whether the mystification would ever disappear. She’s confident it wouldn’t.

“I feel like the mystification is still going to follow it, because whatever age you put it at, it seems like that’s the age you get to and you’re an adult, and people will trust you and respect you, and that’s not necessarily true,” she said.

—

To Blatterer, American attitudes toward alcohol are just one contributor to a system of double binds into which Western societies force youth. It’s often considered normal for young people to act out, and they’re often encouraged to take advantage of their age by doing things adults couldn’t get away with. But at the same time, they’re judged negatively as a “cohort” for acting irresponsibly and immaturely, while adults are never judged as a group for the irregular actions of an individual.

“The experience of a young person is a difficult one, because there’s such a tension between being good and making the most of your young years,” he said. “…That doesn’t mean there aren’t people out there that live extremely straight lives, but if you look at how culture in general creates young people, they’re supposed to be acting out…And then we go and we blame them for it.”

Additionally, according to Blatterer, adults are encouraged to be responsible and stable, even though they have the legal privilege of being able to do things like drink. Bartz said she’s experienced this particular bind since she turned 21—despite the risk of underage drinking, the added financial and social responsibilities of being an adult make it less fun.

“I think I drink the same amount as I used to; I just think about it more,” she said. “Which is weird, because I thought about it a lot when I had to figure out where I was getting it. But I think about it more, I think, now that I’m able to do it for myself—‘Do I have time for this? Can I actually support this for whenever I’m doing it?’”

OWU freshman Bauman said her conversations with international students in the Rotary Exchange Program led her to conclude that the U.S. is a sort of Western anomaly when it comes to alcohol. Of around 30 peers, only three from China and Japan had the sort of “negative association” with alcohol found in America.

“It really is you just have to do everything when you’re young, do as much as you can, but alcohol has to wait,” she said. “And then once you have alcohol, you can experience all the same things again, but then with drinking.”

Moono, a sophomore, said the double bind of youth is actively avoided in Africa—young people are judged based on individual actions rather than generalizations about the entire demographic, so there’s no scapegoat for irresponsibility. Additionally, “recklessness” is often associated with poverty, which encourages “educated people” like college students to act responsibly.

“I think just generally speaking in the African continent and Zambia, that reckless youth thing is not something that your parents or you want to have surround you,” he said. “So when someone is talking about you, that generalization doesn’t exist for the most part. It only exists on an individual basis.”

For Buzalka, youthful recklessness paved the way to adult responsibility. He was put on legal probation for a year following an underage drinking citation he received three months before his 21st birthday. He’s also had law enforcement make fun of him for admitting to being underage when he called emergency services to aid a friend; one officer teased him for having narcolepsy.

Despite these negative experiences, Buzalka said he’s grateful for the lessons he’s learned. He doesn’t drink to excess as frequently, and he focuses more on having fun sober instead of needing alcohol to do so. His brushes with American cultural and legal boundaries surrounding alcohol have taught him the importance of “growing from failure,” a principle he’s carried into his academic and social lives.

“I really like the ideas of how I look at alcohol now, and I personally think they’re responsible and more mature, and I wouldn’t have those ideas if I didn’t have the bad experiences with alcohol,” he said. “If every experience was a great experience, it would be nothing to learn from.”

this one sure help my research about alcohol and american culture! thank you so much!