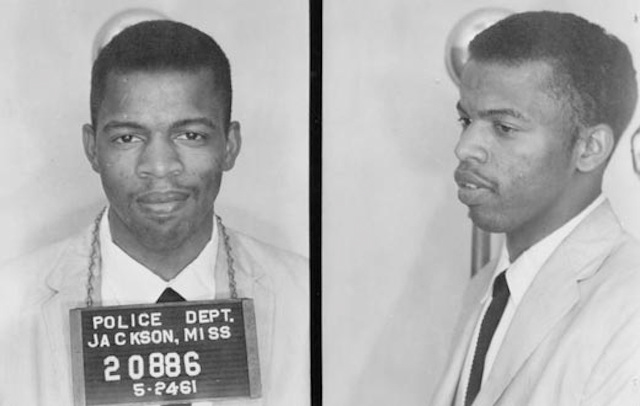

Four days before this, Lewis and other activists – both white and black – were beaten with pipes and baseball bats by a white mob in Montgomery, Alabama while state police watched. Photo: teenagefilm.com

1955

SH: (The civil rights movement began to reach national attention in the 1950s. In 1955, Emmett Till was brutally murdered in Mississippi; he was born a year after John Lewis. Till’s death and the subsequent acquittal of his murderers gained national attention. That same year in Montgomery, Ala., the NAACP and other civil rights groups launched a boycott lasting more than a year after Rosa Parks was arrested for defying segregation on a city bus.) For my generation, we’ve only seen segregation and what that was like in photographs or films, so what was that like and how did it affect you at the time?

JL: When I was growing up, I would see the signs that said “White Only,” “Colored Only”…I didn’t like it, and I asked my mother, asked my father, my grandparents, my great-grandparents why. They would say, “That’s the way it is. Don’t get in the way, don’t get in trouble.” But I was inspired by Dr. King and Rosa Parks and others to get in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble.

SH: Do you think enough is taught in American education today about the civil rights movement and about the legacy of segregation and of slavery before that?

JL: No, I don’t think we do a necessary job or a good job in letting our young people know what happened and how it happened. I think we need to do a much better job, so never again will we repeat the dark past.

1960

SH: (As a student at Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn., Lewis took part in sit-ins to challenge discrimination at lunch counters in the city.) When you started out in the civil rights movement, you were a college student like we are, you were leading sit-ins to challenge segregation in Nashville. What was that like?

JL: Well, Nashville was the first city that I lived in. I grew up in rural Alabama, and to be in Nashville at the age of 17, I literally grew up by sitting down on those wax counter stools. But before the sit-in, we studied. We studied the way of nonviolence, we studied what Gandhi attempted to do in South Africa, what he accomplished in India. We studied Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience,” we studied what Dr. King was all about in Montgomery. And attending a nonviolent workshop before sitting in, I accepted the way of nonviolence, the way of love, the way of peace, as a way of life, as a way of living. And being in Nashville, sitting in and later going on the Freedom Ride, it made me the person that I am today.

1961

SH:(Lewis was one of the first 13 Freedom Riders who challenged segregation in interstate travel.) Why do you think the Freedom Rides were successful?

JL: The Freedom Rides were successful because the American people saw what was happening and they couldn’t believe it. It educated and sensitized so many people and President Kennedy and his brother Robert Kennedy, the Attorney General, responded to the violence – in Anniston, Ala., where a bus was burned, and to the violence that occurred in Birmingham and later Montgomery and the mass arrests of college students, of professors and religious leaders – almost 400 of us went to jail in Mississippi.

SH: Were you surprised by all the violence that the Freedom Riders experienced during that time?

JL: I was surprised about the violence that occurred, but we had been warned. We had been told that we could be beaten, that we could be arrested, that we could die as part of the Freedom Ride.

SH: And what motivated you to keep going, even possibly risking your life to do so?

JL: I was convinced that we could not allow the threat of violence, the threat of being arrested and put in jail, stop a nonviolent campaign to end segregation and racial discrimination.

1963

SH: (As one of the Big Six civil rights leaders, Lewis was selected to speak at the March on Washington as chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. His planned speech, though, contained references to Sherman’s March during the Civil War – still a source of anger for many white Southerners – and questioned the support of the Kennedy administration. Fearing that these remarks would cost the movement needed support, other leaders pushed him to change his speech.) I’m curious how you feel about that now, so many years later?

JL: Well when I look back on it, I don’t have any strong feeling of objection. There were people like Dr. King and A. Philip Randolph, two of the strong leaders within the March on Washington committee, who suggested that we tone down the speech. They said that we (civil rights leaders and federal officials) have come this far together, let’s stay together. I think it was the right thing to do.

1965

SH: (In 1965 Lewis, as SNCC Chairman, worked with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to challenge voting discrimination in Alabama. They led a series of marches. In the first, state police attacked the marchers and protester Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot in the stomach protecting his mother. He died eight days later. The second attempt, was led by Lewis and Rev. Hosea Williams of SCLC. They were crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge when they encountered a line of state police and hastily sworn in deputies.) Can you walk me through what that was like and the violence that followed?

JL: Well, on the day – March 7, 1965 – it was so orderly and so peaceful, 600 of us, I thought we would be arrested and that we would be taken to jail. I was so convinced that we would be arrested that I was wearing a backpack, and in this backpack I had two books. I wanted to have something to read in jail. I had an apple and an orange – I wanted to have something to eat. But we were told by the major of the Alabama state troopers, who said this was an unlawful march and would not be allowed to continue. And Hosea said, “Major, give us a moment to kneel and pray.” And the major said, “Troopers, advance.” And these guys came toward us, beating us with nightsticks, bullwhips, trapping us with horses and releasing the tear gas. I thought I was going to die. I thought I saw death.

SH: I’ve read that you re-walk the route the march was planned for each year. I’m curious what that experience is like to you.

JL: Well, to go back – and I went back just about three weeks ago – to go back there, it’s always so uplifting. It’s so inspiring, especially to take young people and to take members of Congress who have never been to Selma, Alabama, never been to Birmingham, never been to Montgomery. To go back to these historic sites and observe and meet some of the people who participated in it is very moving. You go back and you have to rekindle the spirit that we still have work to do, that we must not stop now.

SH: What was the highest point of your experience in the civil rights movement?

JL: I think the finest moment for me was when we walked across that bridge the third time and made it from Selma to Montgomery. (March 7, 1965 was the second time civil rights workers tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge.) And when Martin Luther King spoke, and then President Johnson spoke, we knew it was a matter of time before the Voting Rights Act would be passed and signed into law. And I was there – he gave me one of the pens that he used to sign the act.

1968

SH: (While they had finally achieved the right to vote, the civil rights movement continued, though it lacked the strength it had in past years. Lewis left SNCC in 1966 but remained involved, helping the presidential campaign of Robert Kennedy, brother of John Kennedy and former attorney general. Martin Luther King was working to build support for his Poor People’s Campaign and went to Memphis, Tenn., to support striking sanitation workers. On April 3 King delivered his “Mountaintop” sermon, describing how he’d seen the promised land, even though he may not reach it himself. The next evening he was shot dead by a sniper.) What was the lowest point of the movement that you felt you experienced?

JL: To witness the loss of people that I got to know, people that I met. I was with Robert Kennedy when we heard that Dr. King had been assassinated. I was in Indianapolis, Ind., campaigning with him on April 4, 1968. Dr. King was my inspiration, my hero, my friend, almost like a big brother and to lose this man changed my life. And I said to myself…“Well, we still have Bobby Kennedy.” Then two months later Robert Kennedy was killed. I admired Robert Kennedy, loved him, and I often think if Dr. King and Robert Kennedy lived the country and the world would be a different place.