Anyone who travels on East Central Avenue in Delaware knows they are in for a bumpy ride. And it’s not going to get smoother any time soon.

City officials know East Central, three blocks north of Ohio Wesleyan University, is a patched mess. The problem, officials said, is where to put the limited money the city has for road projects. There’s money to get potholes patched and cracks sealed, but not nearly enough to provide a long-term fix.

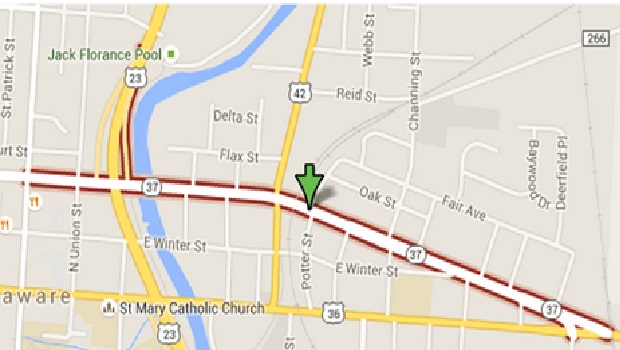

Of the miles of streets in Delaware, the stretch of Central from North Union Street east to where Central joins East Williams Street at “The Point” is striking for its sustained damage.

Documents from the city’s public works department show basic surface repair and maintenance measures have been made, typically filling potholes.

“Central Avenue, with the volume of traffic that it serves, is an area that is constantly monitored for deterioration and the need for repairs,” said city attorney Darren Shulman. “When areas of distress are identified, staff performs repairs to the surface and base courses as deemed necessary.”

The last work order completed by public works employees for East Central – an inspection of an earlier cold patch of a pothole — was on Jan. 15, 2013. The pothole, in the westbound lane of Central near Hammond Street, was patched after a motorist reported blowing a tire because of it.

The city measures the conditions of its roads using a Pavement Condition Index (PCI). The PCI measures pavement condition on a scale of 0 to 100 with 100 representing “new or resurfaced pavement,” Shulman said. By 2013, the most recent available PCI inspection showed a decline in East Central’s pavement condition from 100 to an 86.

According to city records, East Central in 2010 was given the highest inspection rating because the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT), as part of its Urban Resurfacing Program, resurfaced it that year. The city’s participation in the program was limited to partial funding – about $44,000.

“The roads are horrible,” said Hugh Kerins of Delaware and a frequent traveler on Central, “because when the city repairs them, they try to just repair a little spot instead of just redoing an entire section of the road, which after two to five years ends up in the same exact state as previously.”

Kerins said he believes money is available to better maintain the roadways, but said how it is allocated has affected infrastructure in Delaware. He said the city needs help in the form of state and federal aid to stop the crumbling of its road system.

“Take a section every year to work on instead of putting all the money onto the main highways,” Kerins said.

City officials are aware of the problem and grief East Central is causing local residents who live along it and commuters who use it. But officials cite two constraints to solve it: time and money.

“Between Union [Street] and the Point, the reason why that road is not as good as others is because it’s an old road bed dating back 100 years,” said Lee Yoakum, the city’s community affairs coordinator. “If you drive on it, you’ll notice there are no storm water drains nor proper guttering that you may see in other parts of the city.

“What’s happening is groundwater, instead of being drained away, is allowed to filter down into the road base, causing all sorts of issues with moisture and erosion. The end result is that it affects the driving surface.”

A major overhaul would cost tens of millions of dollars and force the city to close that section for months, Yoakum said. It’s money the city doesn’t have. The time needed to do a thorough rebuilding restricts options for rerouting traffic. Repair money cannot be allocated to one project when other streets throughout the city need help.

Officials from across the country earlier this month made a week-long pitch for long-term investment in infrastructure projects. Vice President Joe Biden said on May 11, according to Bloomberg News, investing in the nation’s highways and bridges is a national security issue. Biden said the federal government spends less than 1 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product on infrastructure, which is down from about 4 percent.

“There is absolutely no rationale, no reasonable argument against the need for these investments,” Biden said at a Bloomberg-sponsored event in Washington.

The American Civil Society of Engineers (ACSE), which grades public infrastructure systems on a state-by-state and national basis, said on its website (http://www.infrastructurereportcard.org) that about $3.6 trillion is needed by 2020.

It gave Ohio an overall grade of C- (or mediocre) in 2013, the latest rating available. The ranking also looks at rail, education, dams, parks, wastewater facilities, aviation and energy.

The state’s location as a transit point between the rest of the Midwest and the East Coast is a selling point for state officials when they recruit businesses and industries to locate in Ohio. Ohio’s road network stretches more than 125,000 miles. Ohio’s road network is so large, the ACSE said, it’s about 3.1 percent of the total length of public roads in the United States. The organization said 43 percent of Ohio’s roads are in critical, poor or fair condition.

Delaware’s city engineer and public works director, Bill Ferrgino, said an overhaul of East Central would require a massive deconstruction of the current road. It would include: rerouting of any number of cable, telephone, plumbing, and fiber optic lines that lie underneath the street, a comprehensive installation of a drainage system to keep water from staying in the road bed, and widening of the road itself to accommodate the new levels of traffic it maintains on a daily basis.

“We’re limited on where we can detour traffic,” Yoakum said. “Because Central Avenue is a state route, there are requirements ODOT has as far as street closure and how traffic is detoured. We would not be able to send semis down a side-street and would need to move them to larger routes.”

Ferrigno echoed Yoakum’s comments, but added the city needs federal grant money to aid in an overhaul project. Without federal money, the city can only provide the same road maintenance services it is providing now.

“The city understands the problems facing our infrastructure right now,” Ferrigno said, “and is trying to allocate what we have budgeted to the areas determined to need it the most based off amount of traffic and other factors.”

Major arteries, such as U.S. Route 23 and State Route 37, occupy higher spots on the priority list, Ferrigno said.

Much of the Central Avenue traffic comes from semi-tractor trailers bypassing the frequent stops, greater congestion and traffic lights along Route 23 before moving over to U.S. Route 42. Overweight trucks, as well as tough winter weather conditions, contribute to a growing infrastructure problem in the city.

Based on city’s predictions, 54 percent of the city’s roads will be rated from “Poor to Fair” and “Failed to Very Poor” by 2030. By comparison, in 2009 the physical condition of 43 percent of Ohio’s roads was listed as “Fair” or below, according the ACSC.

The city’ predictions assume no more miles of roads will be added and funding remains the same. But those are dangerous assumptions.

Pulling out a city map, Ferrigno pointed out that from 1995 to 2012, the city added 100 miles of roads. And the number is expected to grow as Delaware County continues to rank as one of the fastest-growing counties in both the state and the country.

According to the city’s operating budget over a five-year period, the public works department began 2009 with $240,000 and of that amount about $26,160 was devoted to berm and asphalt-sealant material. By 2011, the budget was reduced to around $216,000 with $24,000 devoted to the same materials. The current city budget allocation for street maintenance is $334,100, of which $216,300 is devoted to concrete, asphalt and berm materials.