Sara Hollabaugh

Arts & Entertainment Editor

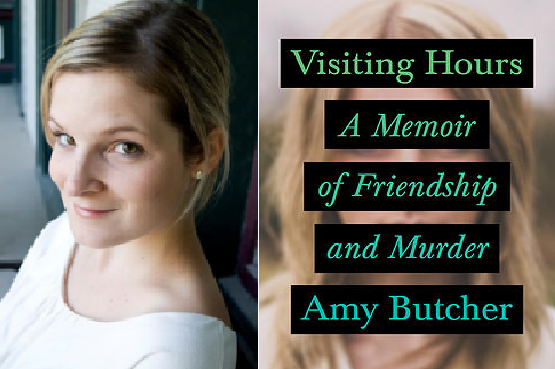

Amy Butcher, assistant professor of English at Ohio Wesleyan, uncovered the difficulty of assigning an emoji via text message to her friend in her most recently published article in The New York Times.

The article, “Emoji Feminism,” does not only showcase the arduous task of deciding what emoji to give her friend, but how the options of emojis for women are limited.

Within the article, Butcher writes that there are in fact emojis for women, but not any for women “engaged in activity or a profession.”

“There [are] only archetypes: the flamenco dancer in her red gown, the bride in her flowing veil, the princess in her gold tiara,” Butcher wrote. “There was a set of ballet dancers complete with bunny ears and black leotards, their smiles indicating that, gosh, they were so grateful to God and everyone, really, for this opportunity to pose for Playboy.”

Butcher was looking for empowering depictions of women to assign to her friend.

“Where was the fierce professor working her way to tenure?” Butcher wrote. “Where was the lawyer? The accountant? The surgeon?”

“How was there space for both a bento box and a single fried coconut shrimp, and yet women were restricted to a smattering of tired, beauty-centric roles?”

When unable to find exactly what they were looking for, Butcher and her friend decided on a penguin.

The anonymous friend of Butcher featured in the article is Ellen Arnold, an associate professor of history at OWU.

“I was proud to have been part of the genesis of this article, although it was a bit odd to be featured (anonymously) in such a major news source,” Arnold said. “One thing that I love about the article, though I’m anonymous, [is that] Amy did a really nice ‘capsule’ version of me.”

“What I enjoyed most was going on Twitter after the article was published and seeing happy and congratulatory penguins everywhere. It shows how much Amy’s voice and concerns resonated.”

Butcher said she truly enjoyed writing the article that raised the question of why there is imminent disparity between men and women, even on the “small screen.”

“I really love comedic writing, and certainly the subject of women in academia,” Butcher said. “The place of professional women within our culture more generally is of great personal interest to me.”

Butcher had both supportive and dismissive responses to her essay in the comments section of the publication.

“Although I had great support from male friends and colleagues, a lot of male commenters predictably complained about the trivialness of the issue, minimizing the larger argument altogether,” Butcher said.

“Some even argued that an adult and professor of English shouldn’t be using emojis in the first place, but I find that argument boring, agist and classist.”

Butcher explained that getting written work into The New York Times is not easy.

“My submission went through what we call the ‘slush pile,’ which is the default email address where thousands of pieces are sent monthly,” Butcher said. “Most often, submissions sent in this way are rejected, but this piece was different.”

The opinion page editor liked Butcher’s article and reached out to her the day after her submission to accept the piece.

“The editor really enjoyed my work and sense of humor and has invited me to send new work to her as I write it,” Butcher said. “I have two pieces I’m in the process of drafting for her, and I’ll send them to her in time, but I have no idea if these new essays will be of any interest to her or not.”

Butcher said that those who are not official writers for the publication do not get re-published for another 3 months. As a professor, that time span is somewhat beneficial.

Butcher has taken after her mentor, John D’Agata, when it comes to being a professor and a writer.

“[He considers] himself exclusively a teacher from September to May and exclusively a writer in the months in-between,” Butcher said.

Being a professor requires a lot of commitment inside and outside of the classroom, which Butcher finds makes it hard to write during the academic year.

“Not only lesson planning, reading and grading, but writing letters of recommendation for past and current students,” Butcher added. “And helping students secure internships and polish off graduate school applications, serving on campus committees, attending readings and plays and recitals, and moreover, just being a helpful presence in a student’s life.”

Senior Adelle Brodbeck, who is currently taking Butcher’s magazine writing class, said it’s great having her as a professor.

“It is so refreshing to have an educator that is close to college age,” Brodbeck said. “It’s much easier to relate to her. Also, it’s nice to have a female professor for once. Out of my four years, the vast majority of my classes have been taught by men.”

Brodbeck enjoyed reading “Emoji Feminism,” as well.

“I thought it was light-hearted and fun, but also had an important message,” Brodbeck said. “In this new age of communication, what are the ways in which we can support each other? Especially how can we support and empower women when the majority of today’s tools are created to favor men.”

As Butcher addresses in her article, sexism has long existed before emojis.

“Emoji diversity is a very small issue plaguing women and our culture more generally,” Butcher said. “But it’s representative of an overwhelming cultural and daily accumulation of grievances.”

“Emojis are the least of it.”

To read Butcher’s piece in The New York Times click here.