Editor-in-Chief

A steel pipe 18 feet long lay on Chappelear Drama Center’s main stage among bare set pieces. A group of seven or eight stood and stared in amazement at its sheer size; two more admired from the catwalk about 30 feet above. All were growing tired—it was getting close to midnight.

Attached to the monolithic rod was a two-foot crossbar, which had to attach to the edge of the catwalk—known as the grid—so the larger piece could hang down above one of the theater’s entrances. It was one of four special lighting apparatuses designed and built specially for “The Passion of Dracula,” the Ohio Wesleyan Department of Theatre’s latest production.

The goal was to get the obnoxiously giant contraption suspended in the air. To do so, it had to be raised 30 feet off the ground first.

The light crew stopped its staring and tried to pick up the pipe. The result was a much less patriotic and much less successful reenactment of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima.

After a brief conference about how best to complete the job, the crew decided a rope would be tied around the crossbar so they could hoist it up to the grid. It was, miraculously, successful—now the pipe just had to be lifted over and attached to a railing about four feet high. Its incredible length made this a Herculean task.

Margaret Knecht, “The Passion of Dracula’s” master electrician and the crew’s fearless leader, supervised from about 15 feet in the air from the Genie, the department’s resident utility lift. The pipe dangled above her head, the crew holding it in a tenuous balance. Her eyes were alert—she was ready to dodge the thing if she had to. She was admittedly a little scared. But she loves moments like these, because they bond the crew in a way nothing else can.

“At the time, I was terrified that people were gonna fall off or it was gonna fall and hit me or something terrible was gonna happen, but we look back on it and we’re like, ‘We almost died that night!’ and we laugh. Bad situations turn into good things, and if you have the right attitude, anything can be fun—even sucky midnight calls.”

Margaret is a junior at OWU from Chardon, Ohio, with an endearingly raspy voice. She likes to wear a lot of black and drink a lot of two-percent milk.

Her first theater experience was as a Jet in “West Side Story” at the age of 6, but she doesn’t consider herself a “theater baby”—someone who was born and raised in the theater.

She joined her high school’s drama club with her older brother as a way to meet new people, and discovered a love for both technical work and performance. She worked on crews for “Nickled and Dimed,” “My Fair Lady,” “Beauty and the Beast” and “Noises Off,” and acted in “You Can’t Take It With You,” “Steel Magnolias” and “The Sound of Music.” She hated “The Sound of Music.”

“My dad calls it ‘Sound of Mucus,’” she said. “It’s really funny.”

In high school, Margaret wanted to be a marine biologist, but decided to pursue theater after a conversation with her high school drama teacher Mrs. Horbath, who introduced her to stage management. She fell in love with management and production in high school because she “loved being in charge”—something she didn’t get from performing.

“It was great in a superficial way to be on stage and get the applause and things like that,” she said, “but I found it more fulfilling to me to be that person behind the curtain that made everything run, that made every aspect of the show come together—the actors, the sound, the lights, everything. I loved being that person, and that might be a little egotistical, but it’s the epitome of what is magical about theater to me—that you can take words on a paper with a script and turn it into a spectacle, or a play that moves people, or just something entertaining. You can just take something so small and make it so big.”

Margaret stage-managed “The Fairy Queen,” the baroque Shakespearean musical spectacle OWU produced in the fall. It’s a stage manager’s job to help the director with anything he or she needs, settle disputes among the company, make sure everyone knows when to be at rehearsals, write a report for each rehearsal and a plethora of other duties. This meant Margaret was in the theater from before 7 until after 10 each night for rehearsals—even earlier and later during tech week, the hellish polishing period in the week leading up to opening night.

Additionally, Margaret had to do what’s known as calling the show—communicating to every member of the crew what to do during the performance and when to do it. “The Fairy Queen” had over 175 light cues, moving scenery, special effects (like a flash pot that almost caught the lead actress’s costume on fire) and myriad other technical elements. Margaret knew every one, backwards and forwards.

Theater puts her under a lot of stress, and can be physically and emotionally taxing. But she said she loves it, simply “because it’s theater.”

“The thing about theater that I’ve noticed, at least for myself, that even the times that I hated it and the times I was extremely stressed out, underneath it all I still loved it,” she said. “I would rather be stressed out about theater than stressed out about schoolwork.”

For Margaret, this zeal is something she can’t put into words. Despite all it takes out of her, it gives something back that she can’t describe.

The only reasons she can give for sacrificing so much are those five syllables: “because it’s theater.”

“I could tell you it’s about the community or about the problem solving or about the fulfillment, but those are just symptoms to the overall disease,” she said. “Those are great, but the passion that I have is something that I can’t explain.”

Margaret came into the department intending to do a performance concentration, but realized she only enjoyed it for the “wrong reasons”—applause and the thrill of performing. Technical work brought her a different, less superficial kind of fulfillment, despite the initial “egotistical” pleasure of being in charge; so she made the transition from getting a lot of recognition to nearly none.

“That hurt—not hurt, but that was a little bit of a twinge for a little while,” she said.

“But I’ve progressively gotten over it, because I would rather—not even just get praise—but I would rather be recognized by my peers in the department than the audiences. Because I loved being that person that people felt that they could count on, because I feel like I’m a pretty trustworthy person. So being able to be there for this department and being able to help the show run and being recognized by my peers—people that I actually want their respect, and their respect actually matters to me.”

Margaret didn’t abandon acting completely—she appeared in the infamous “Mame” her freshman year, and played Madame Desmortes in last spring’s “Ring Round the Moon”—so she occupies a unique position in the eternal feud between actors and “techies.”

The two distinct groups often quarrel because they each form tight bonds over the course of rehearsals and late-night calls. While both come together as a cohesive unit to put the show on, Margaret said, they exist in separate spheres.

“Sometimes it’s like, ‘Techies unite! Actors unite!’ And techies will take jabs at actors, and actors will take jabs at techies,” she said. “We’re under a full community. I don’t want to make it sound like we’re segregated. I’m both an actor and a techie, and it’s really fun to make jabs either way.”

Kristen Krak has bridged the gap between techie and actor, too. She stage-managed the 2012 One Acts, a collaborative production by the Directing and Playwriting classes, as a freshman. It was much less demanding than “The Fairy Queen,” but still required gaining a good deal of knowledge on a steep learning curve.

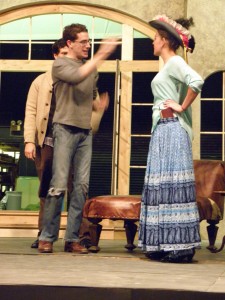

More recently, Kristen’s stuck mostly with acting. She played Hermia, one of Shakespeare’s Four Lovers, in “The Fairy Queen,” and will star as Wilhelmina in “The Passion of Dracula.”

Kristen is a sophomore from Granville, Ohio. She loves cats, plays guitar and has a small nose piercing, a popular body modification among the theater department.

Kristen said she started dancing around age four. She gave her first ballet recital when she was five, and got her first acting experience as the Mouse Queen in a local production of “The Nutcracker.”

Being on stage from such a young age made performance natural for her. She wanted to go into genetics in high school, but her youth pastor’s wife—like Margaret’s Mrs. Horbath—made her realize theater was her true passion.

Her parents questioned her decision to make such a drastic change, and she still hesitates herself—as one who describes her “inner nature” as caring and nurturing, she sometimes wonders how she is “directly helping people” through theater.

In her senior year of high school, Kristen worked with a special education class of developmentally disabled students her age. She befriended a 16-year-old autistic girl named Lauren, who didn’t talk much, but often amazed Kristen with what she could do—once, she spilled a jigsaw puzzle onto the floor and solved it within five minutes.

“Like, it was a huge puzzle,” Kristen said.

“And she just sat there and just twisted them, twisted them, picked up another piece, twisted them—I just stood there open-mouthed, like, ‘Did she do this? Has she done this puzzle before?’”

Soon after working with Lauren, Kristen started volunteering at a theater program for autistic children. The staff would rehearse a fairy tale with a younger group of 8- to 12-year olds, and a high-school age group would practice a portion of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

Kristen worked with a boy there named Jake. To help him memorize his lines, she read one to him while he was coloring and he’d repeat it. He would never look at her while they rehearsed, so she thought he wasn’t retaining anything.

“And I did it again, and did it again, but he still wasn’t paying attention to me, and I was like, ‘Alright Jake, tell me.’ And he just looks at me and spits out the whole monologue. I was like, ‘Point proven. Point proven.’”

Kristen said she’s read extensively about how working with characters can help children with autism like Jake and Lauren improve their communication skills and deconstruct “social barriers.” These sorts of programs are the answer to her question about how theater can help people.

“My two greatest passions in life are theater and autism, and it just so happens that they fit together very nicely,” she said.

Kristen finds working with characters liberating for her, too—the opportunity to be someone else makes it less intimidating to perform, even when performance is so natural.

“I don’t mind giving a presentation, but if I have to get up and talk about myself, that’s when I get nervous,” she said. “…But when I’m another person, when I’m playing a character, then I really don’t have a problem with it.”

Acting gives her the opportunity to have an extraordinary existence for a short time, an escape from her “solid, mediocre, decent life.” It’s a way to live in extremes and “be somebody exciting.”

But it can also put things in perspective. When she was a freshman in high school, Kristen played Emily in “Our Town,” a metaphysical play by Thornton Wilder about “life and looking back on life.” When she was in the show, a boy in the junior class at her school had just died in a car accident.

The play’s theme of life’s impermanence was jarringly relevant to these events—Kristen remembers crying after rehearsal one evening.

“I don’t think I would have gotten as much out of that play if that hadn’t happened like that,” she said. “But it really affected me and struck me and reminded me—the whole moral of the story was very true at that point…. I think it gave me the ability to help others, too, at that time, other people in my high school.”

The show made her realize how cathartic and healing theater can be for anyone—not just members of the company, but those in the audience, as well. A well-executed drama can make a viewer feel as if they’re not alone in a dark situation, and a good laugh at a comedy can cheer them up.

“I think that’s exciting as an actor—how is what you’re doing going to affect others?” Kristen said. “I think that’s a huge part about theater, is the effect that you reveal is the impression, the thoughts.”

As much positive power being in character has for Kristen, having to let go of a character has a lot of negative power for actors—especially Matthew Jamison.

“The day after the last performance I wake up and it’s like I feel like I’m gonna die, like my life has no purpose anymore because this thing that I have sacrificed for and put my whole entire being into doing is done, and it’s horrible. It’s a horrible feeling.”

Matthew is a junior from Houston, Texas. He spent the fall semester in Europe, and he thinks in lists.

For Matthew, the thrill of performing makes up for every sacrifice he makes for the theater. He describes it as “ephemeral”— “It lasts one moment, moment to moment, and it’s never exactly the same way again.”

This ephemeral nature of theater is why he wouldn’t let his parents watch the recording of his performance in last fall’s “Dear Brutus.”

“Because it becomes something—it’s not the play we did,” he said. “It’s something different. It’s not ephemeral once you film it. It’s like a completely different entity.”

Matthew was very much the theater baby Margaret wasn’t—his parents loved theater, and one summer sent him to a one-day musical theater camp against his will. In the end he loved it, and went back for every remaining session.

As a child, he acted in local community theater, where he was “exposed very early to drunken, naked adult actions, most of them gay.” He also worked in a few professional productions when children were needed, like “The Wizard of Oz.”

Community theater, he said, helped him learn a good deal about acting while avoiding “the nonsense of doing theater”—overstretched budgets, tight deadlines and poor “artistic choices.”

Matthew was exposed to that nonsense as a junior in high school, when he participated in New York’s Broadway Theater Project, a program run by professional directors and choreographers. He expected insightful advice that would help him on his way to a BFA in theater performance; he got something very different.

“It was miserable, because everyone was very jaded, like, ‘Yes, I’m a Broadway casting director and that gives me the right to be an asshole to everyone.’ So it was very mean-spirited, and it was like, ‘This is how you do musical theater, and any deviance from this is wrong, and you’re a bad performer if you deviate from this.’”

He recalls a particularly bad session with Frank Wildhorn, who composed “Jekyll and Hyde” for the Broadway stage. Wildhorn talked about how he wrote a song for that show simply because his producers wanted a piece audiences could recognize. This sort of selling out, capitalizing on theatrical art, is what Matthew calls “shitty theater.”

“I don’t wanna perform in shitty theater. I love musical theater, but I like a very small number of musicals. So yeah, I’d love to perform in musicals all day, but I don’t wanna perform in ones that are being produced professionally….(B)ecause it’s all based on money and bringing in people, so I would be a performer, but I can’t make a living performing the things that I want to.”

Some in the OWU theater department call Matthew a triple threat—a performer who can sing, dance and act exceptionally well. Despite this, he wants to teach rather than perform for fear of being sucked into this “shitty theater” as a means of sustaining himself—plays that aren’t shitty to exist, he said, but they exist in warehouses and aren’t a viable career path. So the faculty at OWU inspires Matthew to achieve his goal of professorship.

Some in the OWU theater department call Matthew a triple threat—a performer who can sing, dance and act exceptionally well. Despite this, he wants to teach rather than perform for fear of being sucked into this “shitty theater” as a means of sustaining himself—plays that aren’t shitty to exist, he said, but they exist in warehouses and aren’t a viable career path. So the faculty at OWU inspires Matthew to achieve his goal of professorship.

“I kinda wanna be like a mash up of Bonnie and Ed—do literature but also theories…I’m really into educational theater, too, and Bonnie does that. But my favorite parts of both Bonnie and Ed.”

Bonne Milne-Gardner is an accomplished playwright and a member of the Dramatists Guild of America.

She is Ohio Wesleyan’s resident expert on playwriting, dramaturgy, theater education, arts management and other subjects, according to the university website.

Ed Kahn began his theater career after working as an engineer. He has a Master of Fine Arts degree from Northwestern University and a Ph.D. from Tufts University. He teaches Directing and Theories of Performance at OWU.

Matthew said the faculty’s openness and expertise make them easy to work with in shows and serve as models for the kind of teacher he wants to be. They’re flexible, but not too flexible; they know what they want for themselves as directors, but are willing to make the student’s experience as close to ideal as possible.

“They are open to giving you the experience that you want within the framework that they want,” Matthew said.

Gus Wood does not feel so fondly.

“I honestly feel like at least some of the faculty here has forgotten their first priority at an institution of education, which is education,” he said.

“I feel like when a show goes up, or when a show’s going up, they’re so focused on doing the job of the show that they lose track of the fact that we’re all trying to learn from that process.”

Gus is a junior. He does performance poetry, and had the nation’s second-best haiku in 2011. The destination of his daydreams is Milk World, a universe where everything is made from dairy products.

Gus was first drawn to theater because of its power to make him cry. When he was young, his sister acted in “A Christmas Carol,” and the actor playing Jacob Marley made him burst into tears. He pursued it throughout high school and fell in love with theater as an art form, as “the most honest, engaging, powerful thing I have ever experienced.”

Gus’s freshman year was when “Mame” happened. “Mame” was a disaster.

“All you essentially have to do to elicit a Pavlovian groan from anyone in this current stock of theater majors, junior and above, is say the word ‘Mame,’ and there will be a groan so palpable that you can grab it, strangle it and ask it questions,” Gus said.

“Mame” is a 1966 musical by Jerry Herman; Elane Denny-Todd directed the OWU production in the fall of 2010. Rehearsals started at 7 p.m. and had no designated end time, so the cast had no idea when they would be allowed to leave. The show was also “technically demanding,” Gus said—“We had a staircase, for Christ’s sake.”

Elane is one of the OWU faculty whom Gus feels has lost a sense of collaboration with her students over the years.

“You have an idea of the show,” Gus said of some experienced directors, “and it’s a very concise, narrow, complete idea—it’s even a good idea—but if anyone has something that isn’t that idea, it kind of throws a wrench in your machine and you have to think about it, and that bothers some people.” Elane, according to Gus, is someone it bothers.

Gus feels the cast must claim some responsibility in such situations, that it would be possible for a group of upperclassmen to approach a director with ideas of how to make the experience better for the company.

But most don’t say anything because they’re “(s)cared of making waves, scared of causing problems for themselves later.”

One step out of line could have lasting effects on one’s career.

“Because one ‘Hey, I think you might wanna check yourself on that,’ could turn into ‘Hey, I’m not gonna cast you in that show next year,’” he said.

Gus said directors in the OWU department often make shows feel like work rather than a learning experience, and it often becomes hard to separate the stress of producing a show on a deadline from academics.

“(T)hat atmosphere pervades into the classroom, because the guy who yelled at me last night about how I don’t know how to focus a light is trying to teach me something else the next day,” he said. “Like, that level of impatience is still gonna be in my mind, and I’m not gonna want to ask questions, and I’m not gonna want to ask him to go over it a third, fourth, fifth time even though I need it.”

Gus came into OWU as a theater major and English minor. He’s now reversing the two, dropping theater to a minor and pursuing English fully. He said the way the department teaches its students isn’t conducive to learning for him. He said he spends most of his class time “either competing with the people in my class, or…feeling inferior about the things I don’t know.”

“(H)ow they could’ve kept me here is just understand that I, personally, as a student, need to fuck up nine times before I get a really good tenth time,” he said.

For Gus, theater at OWU has crreated a lot of good memories—many of his friends came from theater, and his contemporaries have become “like a family.” The department simply showed him that his future is in a different place, doing something else.

“Honestly, for me, I feel like I would’ve gotten here eventually,” he said. “This place made it go a hell of a lot faster…. I’m not walking away from this department howling and cursing and spitting and shitting. I am extraordinarily grateful for the good experiences, a tad resentful and regretful about the bad ones, but I’m not about to hold anybody more accountable than myself.”

Gus still believes in theater. He believes in its power as art, and the “sense of expression and vulnerability” it offers. And he believes in its power to send a message.

“This is gonna come off a Hallmark card, but none of us would be here if we didn’t feel we had something to say, and since everyone here has something to say, ideally—and I believe it’s true of this department, at least to some extent—if everybody believes they have something to say, everyone is willing to listen to somebody else.”

Caroline Williams is a freshman from Hudson, Ohio. She often wears a rainbow beanie that one of her friends sometimes steals off her head. Her biggest inspiration is her mother.

She started doing theater her sophomore year of high school—when she was still an introvert—doing sound with her friend Rachel, who she “sat in the corner with and didn’t talk to anyone with.”

She continued to do technical work, and interacting with the community in her department built up her self-confidence.

In her junior year she auditioned for and got a leading role in one of the school’s plays. This was the first time she had ever gotten “a big head.”

“But I think it was kind of good for me to have a big head at that point, and I think it’s easier to go up and come down a little bit than to just get myself to the regular point,” she said. “So I think it was nice to be coming down from having way too big of a self-esteem and figuring it out—I think I needed that, ‘cause it was a big step to think anything great of myself, ‘cause I had a really low self-esteem early in high school and before high school.”

Caroline is doing a tech concentration in theater at OWU, but she took Elane’s Beginning Acting class this past fall. There she learned how words are just another of one’s actions on a stage, and how every action—including speech—is significant.

“You don’t just move for the sake of moving,” she said. “You move to say something.”

Caroline is also an English major, so this was a difficult idea for her to grasp—she was used to thinking words were something inherently more powerful than movement. But her experience in theater has helped her learn that different people “understand the world” in different ways.

“(W)ords and theater—that is my way of understanding the world, and getting ideas. If I have a feeling about (something) in my personal life, or about social justice, I would write a play about it, and that would be how I send a message,” she said.

“Or I might write a poem about it. Some people, in terms of understanding the world and why we’re here, they do that through math equations, and that’s how they understand the world, and that’s what they feel is important. And I think that’s just as valid—if how you feel you can understand why we’re here and what’s around us, if that’s through physics or chemistry, or anything, that’s just as valid and important as me seeing it through a theatrical production in front of me, or someone who sees it through color on a canvas.”

Caroline worked on the second OWU production of “8,” a play by Dustin Lance Black about the legal battle against California’s ban on same-sex marriage. As an activist for marriage equality, she felt it was an important message to send, but she doesn’t feel theater should force the audience to think a certain way—it must “walk a line of getting people to agree with you,” but shouldn’t push them over it. Because of her respect for different understandings of the world, this is something Caroline said she’s going to be careful of.

“I think that what I’ll have to really think about in what I’m doing is not trying to get people to believe things, but telling them the truth and then maybe they’ll come out of it believing the same thing as me, or at least having an opinion,” she said.

“Because I’d much rather come out of a show thinking completely opposite of what I think that being indifferent about it.”

Caroline feels, though, that theater has an inherent power to bring such daunting social issues close to home and make them intensely visible to an audience. Because theater focuses in so tightly on human relationships and experiences, it makes it easy for the viewer to see a story up close and relate to it.

“I think theater often zooms in on the individual emotions of people in a situation, instead of just a broad statement about what happened,” she said.

As something that focuses so closely on individuals, Caroline thinks the theater is a place where one has to “be able to put yourself out there and be a little weird,” to establish an identity as an individual.

But at the same time, it’s welcoming—everyone has a place.

Caroline thinks these open arms should be carried through the auditorium doors because they’re so universal.

“I think it’s kind of been a really nice starting point for a lot of people that I’ve known, of being able to find a place in something,” she said, “and then taking it past theater and being like, ‘I can find a place other places, too. I have things to add, and people value me.’”

Caroline was on the light crew for “The Passion of Dracula.” She was there holding onto that pole for dear life with everyone else—without her, it would have likely knocked Margaret off the Genie. She was the anchor, and when she faltered, someone had to take the weight for her.

She was there, and she had a place. Everyone did.